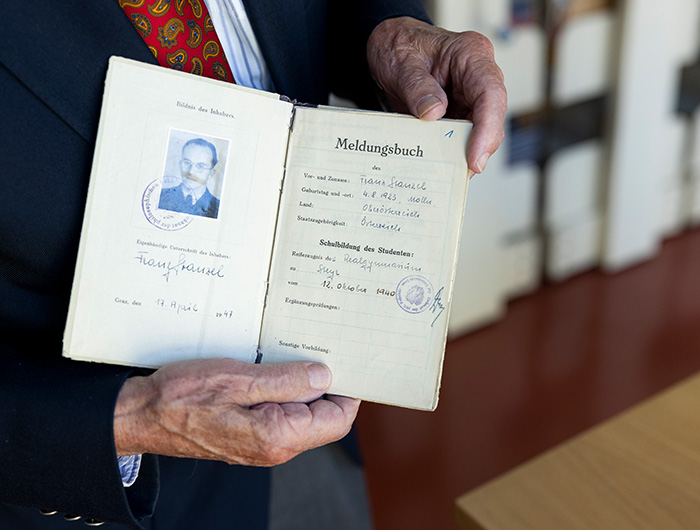

Franz Karl Stanzel

Alumni in portrait November 2021

From prisoner of war to the lecture hall

His "Theory of Narrative" is still THE standard work for students of literature. The foundation for his academic career was laid by four years as a prisoner of war in England and Canada. Today Franz Karl Stanzel is 98 years old. How did Austria's best-known English scholar experience his own student days at the University of Graz immediately after the Second World War? A contemporary witness document.

Prof. Stanzel, as a schoolboy you demonstrated for Austria's independence, and were even interrogated by the SS for this reason in 1938 after the annexation of Austria. And then in 1940, at the age of 17, you volunteered for the navy. Why?

"Voluntary" is not quite accurate. It was more like an escape to the navy. There was compulsory military service and I knew I would be drafted after graduating from high school. Putting on a steel helmet and marching - that was unimaginable for me. Coupled with a certain romantic wanderlust, I decided to join the navy.

A good decision, even if it didn't look like it at first.

Yes, in 1942 I served on the submarine U331, which was sunk by the British off Algiers. Of the 49-man crew, 16 survived - and only because an English pilot disobeyed his orders. He should have picked up only two "token-prisoners," two men who could prove which boat it was and who was in command. But he pulled as many survivors out of the water as he could. And when his plane was so full he almost couldn't take off, he called in a destroyer to pick up the remaining men. I was one of them.

Luck in misfortune. This is also how one could describe the subsequent time as a prisoner of war in England and Canada.

In fact, those four years were crucial to my academic career. My very first encounter with English poetry - with William Wordsworth, to be precise - took place in the Grizedale Hall prison camp in Cumberland. And in Canada, I benefited from the camp's extensive library. There were, for example, scholarly annotated editions of Shakespeare's works. Studying them replaced an entire proseminar.

Why did you get involved with English literature while you were a prisoner of war?

On the one hand, you had to keep yourself busy somehow. Although I was not an officer as a midshipman, I was sent to an officers' camp. As an "ordinary" soldier, I could have been called upon to work outside the camp. However, I was not allowed to leave the officers' camp. On the other hand, I also slowly began to think about how things could continue after the war. The course of the war made it increasingly clear that a career as a naval officer was obviously not going to happen. I had already studied the English language in great detail beforehand, and from this arose the desire to study and become an English teacher. And I began to prepare for this already in the prison camp.

I went to the University of Graz in the summer semester of 1947. How did you actually finance your studies back then?

In 1947, the maximum amount that could be withdrawn from a savings account was 150 shillings a month. Although I was allowed to live with friends for almost nothing - that was too little to live on. That's why I started working as an English teacher for emigrants in a refugee camp of the International Refugee Organization in Trofaiach. There I earned about 900 shillings a month.

How can you imagine the situation at the university at that time?

The conditions were really desolate. There was a shortage of everything, especially qualified personnel, since a number of professors had been dismissed for Nazi party membership and many assistantships had been cut. The English Department consisted only of the director, Prof. Herbert Koziol, and one research assistant. English lessons were given by the hour by two English lecturers. However, there were 90 to 100 English students to "take care of". This number doubled in the next five years. Also characteristic of the time was an episode in my first literature lecture in German Studies. Instead of Goethe, as expected, there was a telling off from the professor because no volunteers had come forward to cart coal from the main train station for the furnaces at the university. I then joined forces with a group of colleagues, significantly all war returnees; we shoveled coal into sacks at the station and moved with two handcarts through Kepplerstrasse to the university. That was my first contribution to university studies, so to speak (laughs).

What was the offer at German Studies basically like at that time?

To put it politely, very conservative and uninteresting. The emphasis was on language history and positivist literary history. For example, I attended a four-hour lecture on the phonetic history of German. Since the professor did not speak very clearly and did not even turn around to write, say, a phonetic development on the blackboard, we made do by always reserving the first row in the lecture hall for several "scribes" who then produced a script together. But nobody thought of protest at that time - the war returnees were used to silent obedience. It was only around 1969/70 that this situation changed with the student protest movement of the time.

At that time, German studies were the very worst, not only in terms of content, but also pedagogically. English studies was well supplied with linguistic history, but literary fare was meager. An aha experience for me was a guest lecture by the Scottish author Edwin Muir. Afterwards, we - a group of five or six students of English and German - talked briefly with Muir, and he asked us point blank: "What do you think of Kafka?" Our response was, "Kafka who?" This was 1947, and although "The Castle" was already on the required reading list of Germanists at some American colleges at that time, we had never heard of Kafka. During the Nazi era, his books had been removed from libraries.

Half of the male students at the time were war returnees. Did they talk among themselves about their personal war experiences?

No, me personally and my closest friends - never. Looking back, I also notice that I almost only had contact with war returnees. We were our own troop, without consciously wanting to set ourselves apart. But we hardly ever said a word to each other about our war experiences. We wanted to put all that behind us. Instead, we talked about topics that interested war returnees at the time: livelihood, women, politics, in that order. At first, we approached the already considerable number of female fellow students somewhat shyly. I myself had no contact at all with the female sex in the formative years of manhood from 17 to 21. That was simply a loss that had to be worked through psychologically. I think I succeeded in doing that, but it wasn't easy.

The year 1949 then finally steered your path in the direction of a university career. And again, a happy coincidence was the deciding factor.

Yes, you could say that (laughs). I was a prisoner of war together with the Austrian novelist Mario Wandruszka. He was released a little before me and gave me the parting advice, "If you want to do English studies, you have to study the Luick!" Karl Luick was a prominent Viennese language historian and teacher of Herbert Koziol. There was no advice or introduction to the study at that time, and so I probably took the advice too eagerly. At some point, my "over-information" on phonetic history did not go unnoticed by Prof. Koziol, and he offered me the position of the only research assistant in the house, for 502 shillings a month. With this pittance I crawled into the academic career, so to speak. At that time, I had no idea that I would not get out of it until my retirement in 1993.

What kind of job was it back then?

The research assistant was not an assistant position, it had been cut during the war. I was the girl for everything: librarian, secretary, stoker and janitor, responsible for setting up and locking the rooms of the seminar, which at that time were still in an apartment building at Heinrichstraße 36. Also a curiosity of the time: in the beginning, Prof. Koziol lived in the library with his wife and their two children. And so I always had to ask Mrs. Koziol to clear away the boys' beds in order to get to the Shakespeare (laughs).

Your time as a student cannot be compared with anything that generations of students have experienced since. What was actually the most formative experience for you during this time?

I had only been working as a research assistant for a year when, for the first time, U.S. Fulbright scholarships were also announced for Austria. Without hesitation I applied and again it was a lucky coincidence that got me a fellowship place that would have a very decisive influence on my further career. It happened like this: I had chosen "Das Amerikabild Thomas Wolfe 1900-1938" as my dissertation topic. Instead of a cheaper fellowship to one of the State Universities, I was awarded a fellowship to the elite Harvard University. Apparently Thomas Wolfe was a Harvard graduate and the Fulbright Commission wanted to allow me to do further research on his novels "on the spot." Which I didn't, however. There was so much else, more interesting. Harvard literally meant an intellectual rebirth for me.

In what way?

I came to this country with an idea of literature that was completely inadequate. In Europe at that time, positivism dominated literary studies; novels were interpreted primarily according to the data and facts that could be read from the author's history and interests. In America at that time, in the spirit of New Criticism, preference was given to text-immanent interpretation. Moreover, structuralism was already making headway at that time. Without this experience, my work as a literary scholar would have been unthinkable. America also had a personal impact on me. Until then, I had only known existential hardship and a lack of demands. And suddenly I was in a country where milk and honey flow, so to speak, materially and intellectually.

In 1955, the "training period" at the University of Graz ended with the habilitation under Prof. Koziol with "The Typical Narrative Situations in the Novel". When, in your 99th year, you look back on your eventful biog

That's a million-dollar quest ... very difficult. I am fully aware that my world, because of my very special experience, was so uncharacteristically destined. To reconstruct from that a maxim of life that could be passed on to present generations is very difficult for me. From the point of view of literary studies, this would be relatively easy: here, it is probably primarily a matter of discovering something in a poem, a novel or a drama that can be explained not only historically, but structurally. In doing so, it is easier to arrive at new insights. But from a human point of view, the question can hardly be answered. What was decisive for me in the end were things that came about because of my very unusual background. They don't apply to a young person today. For example, my choice to join the navy at that time. That was like a blind chicken picking a seed that became very fertile. My extraordinary life story "deformed" me as a counselor, you might say. The world is a very different place today.